Meaning of Don't Throw the Baby Out With the Bathwater

It hits your email inbox with surprising regularity: "Life in the 1500s," a collection of the incredible stories behind old sayings like "throw the baby out with the bath water" and "chew the fat." "Incredible" is the operative word. The stories are amazing; too bad they're not true. Here's the real scoop behind the first set of the expressions in this prank email.

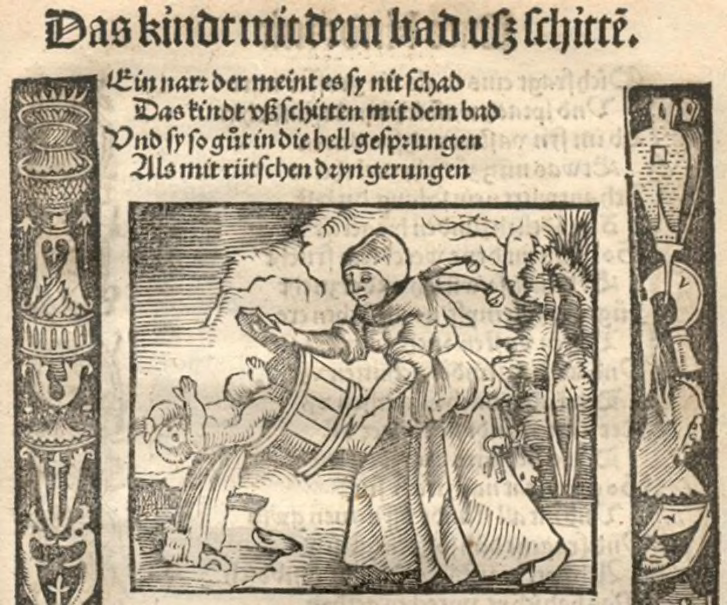

1. To throw the baby out with the bath water

Wikimedia Commons

The Tall Tale: Baths consisted of a big tub filled with hot water. The man of the house had the privilege of the nice clean water, then all the other sons and men, then the women and finally the children—last of all the babies. By then the water was so dirty you could actually lose someone in it—hence the saying, "Don't throw the baby out with the bath water."

The Facts: In the 1500s, when "running water" meant the river, filling a large tub with hot water was a monumental task. A wet-cloth version of a sponge bath was all most people could manage. In the 19th century, English writers borrowed the German proverb "Das Kind mit dem Bade ausschütten] [to throw the baby out with the bath water]." The saying first appeared in print in Thomas Murner's satirical work Narrenbeschwörung (Appeal to Fools) in 1512. Judging from the woodcut illustrating the saying, mothers were able to fill a tub large enough to bathe a baby, but the child could hardly be lost in the dirty water.

2. To rain cats and dogs

Wikimedia Commons

The Tall Tale: Houses had thatched roofs—thick straw, piled high, with no wood underneath. It was the only place for animals to get warm, so all the dogs, cats, and other small animals (mice rats, and bugs) lived in the roof. When it rained it became slippery and sometimes the animals would slip and fall off the roof, hence the saying "It's raining cats and dogs."

The Facts: Mice and rats (not cats and dogs) did burrow into the thatch, but even they would have to be on top of the thatch to slide off in the rain. Etymologists offer several theories about the origin of the phrase, which first appeared in print in the 17th century, not the 16th:

• It could refer to the well-known enmity between two animals and so allude to the fury of "going at it like cats and dogs."

• William and Mary Morris suggest that the phrase arose from the medieval belief that witches in the form of black cats rode the storms and from the association of the Norse storm god Odin with dogs and wolves, but since the expression appeared so late, these seem unlikely sources.

• Gary Martin, author of the Meanings and Origins section of the Phrase Finder website, states that there is no evidence for the theory that "raining cats and dogs" comes from a version of the French word catadoupe, meaning waterfall. Instead, Martin proposes that, "The much more probable source of 'raining cats and dogs' is the prosaic fact that, in the filthy streets of 17th/18th century England, heavy rain would occasionally carry along dead animals and other debris…Jonathan Swift described such an event in his satirical poem 'A Description of a City Shower,' first published in the 1710 collection of the Tatler magazine."

• But then again, Swift was noted for his flights of fancy and the phrase had been used since the mid-1600s. Perhaps these elaborate backstories are gratuitous. "Raining cats and dogs" may simply be an imaginative way of describing a pounding storm.

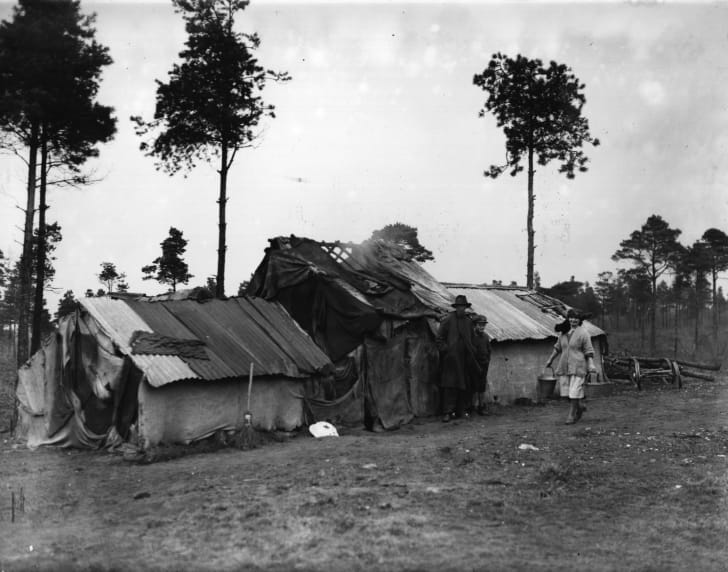

3. Dirt poor

Getty Images

The Tall Tale: The floor was dirt. Only the wealthy had something other than dirt—hence the saying "dirt poor."

The Facts: In the simplest cottages, the floor might be packed dirt, but those who could afford them had wooden floors. "Dirt poor" is an American expression first documented in the 1930s, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, and a search of Google Books backs up the claim.

4. Threshold

The Tall Tale: The wealthy had slate floors that would get slippery in the winter when wet, so they spread thresh on the floor to help keep their footing. As the winter wore on, they kept adding more thresh until when you opened the door it would all start slipping outside. A piece of wood was placed in the entry way—hence, a "thresh hold."

The Facts: The wealthy had wooden floors. The boards were rough, so they were covered either with carpets or, yes, rushes or reeds, but these were usually changed daily. Although in Scots dialect reeds were sometimes known as "thresh," threshold has a different origin. It comes from therscold or threscold, which is related to German dialect Drischaufel. The first element is related to thresh (in a Germanic sense, "tread"), but the origin of the second element is unknown.

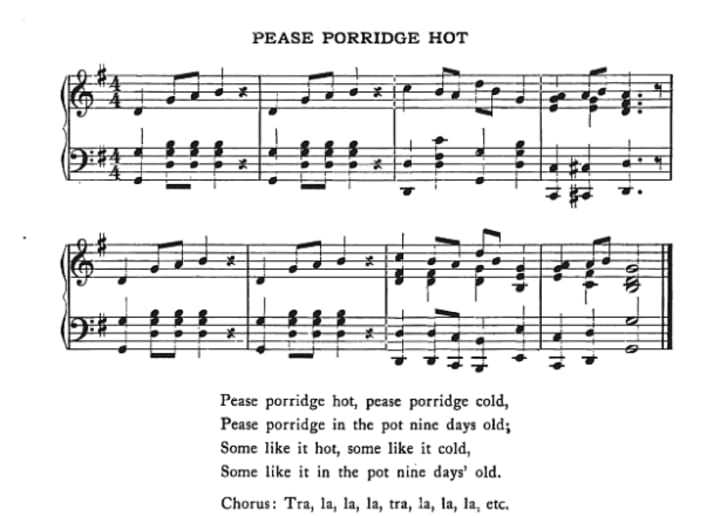

5. Pease porridge hot, pease porridge cold

Wikimedia Commons

The Tale: They cooked in the kitchen with a big kettle that always hung over the fire. Every day they lit the fire and added things to the pot. They ate mostly vegetables and did not get much meat. They would eat the stew for dinner, leaving leftovers in the pot to get cold overnight and then start over the next day. Sometimes the stew had food in it that had been there for quite a while—hence the rhyme, "peas porridge hot, peas porridge cold, peas porridge in the pot nine days old."

The Facts: OK, this one is actually true (except for the claim that anyone likes it cold). Pease, as it's often spelled in the chant, is an archaic spelling of "peas," so pease porridge is what we now call "pea soup."

6. To bring home the bacon

Getty Images

The Tall Tale: Sometimes they could obtain pork, which made them feel quite special. When visitors came over, they would hang up their bacon to show off. It was a sign of wealth that a man "could bring home the bacon."

The Facts: Some writers trace the expression "bring home the bacon" to catching the greased pig at a fair and bringing it home as a prize. Others claim the origin is in an English custom dating from the 12th century of awarding a "flitch of bacon" (side of pork) to married couples who can swear to not having regretted their marriage for a year and a day. Chaucer's "Wife of Bath" refers to the custom, which still survives in a few English villages. One problem, though: The phrase did not appear in print until 1906, when a New York newspaper quoted a telegram from the mother of a prizefighter telling him "[Y]ou bring home the bacon." Soon many sportswriters covering boxing picked up the expression.

7. Chew the fat

Wikimedia Commons

The Tall Tale: They would cut off a little [bacon] to share with guests and would all sit around and "chew the fat."

The Facts: The Oxford English Dictionary equates "chew the fat" with "chew the rag." Both expressions date from the late 19th century and mean to discuss a matter, especially complainingly; to reiterate an old grievance; to grumble; to argue; to talk or chat; to spin a yarn. J. Brunlees Patterson in Life in the ranks of the British Army in India and on Board a Troopship (1885), speaks of "the various diversions of whistling, singing, arguing the point, chewing the rag, or fat." In other words, "chewing the fat" is an idle exercise of the gums that produces little nourishment.

Sources: Domestic architecture: containing a history of the science; "Flitch of Bacon," Wikipedia; "Housing in Elizabethan England," Daily Life through History;Google Books Ngram Viewer; The Phrase Finder; Snopes.com; Morris Dictionary of Word and Phrase Origins, 1971; New Oxford American Dictionary, 2nd ed.; Oxford English Dictionary Online.

Meaning of Don't Throw the Baby Out With the Bathwater

Source: https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/55503/7-tall-tales-about-life-1500s-and-origins-phrases

0 Response to "Meaning of Don't Throw the Baby Out With the Bathwater"

Post a Comment